Second homes and year-round desertification: are Breton villages in danger?

- Roland Chevallier

- 8 sept. 2025

- 4 min de lecture

For several years, Brittany has held a special place in the hearts of French people seeking a second lease on life. With its wild coastline, traditional architecture, quality of life, and deeply rooted culture, the region is attracting more and more buyers. But behind this appeal lies a more worrying reality: the continued growth of second homes is often accompanied by a loss of residential dynamism, particularly in coastal and rural communities.

With some villages boasting over 50% of homes occupied for only a few weeks a year, the question arises: is Brittany becoming a region of second homes to the detriment of its permanent residents? And, above all, what are the consequences of this phenomenon on the balance of territories?

An explosion of second homes in Brittany

An old phenomenon, but one that is accelerating

Buying second homes in Brittany is nothing new. As early as the 1970s, families from the Île-de-France region, Nantes, and Rennes were buying houses on the coast for their holidays. The beauty of the coastline, the relative affordability compared to other seaside resorts, and the family or cultural ties maintained with the region have fueled this trend.

But since the 2020 health crisis, this phenomenon has accelerated considerably. The massive increase in teleworking, the desire to move away from major cities, and the quest for nature have led to a veritable rush for homes by the sea or in the countryside. Many properties, once vacant or abandoned, have been renovated to become leisure residences, or semi-permanent "pied-à-terre" for city dwellers seeking escape.

Figures that speak for themselves

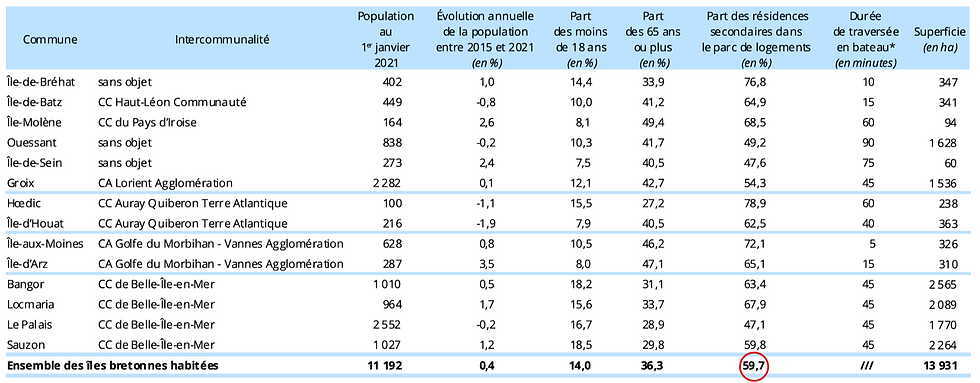

Statistics confirm this dynamic: according to INSEE, Brittany today has nearly 300,000 second homes , representing around 14% of the regional housing stock , a figure well above the national average.

But this percentage rises sharply in coastal towns: in certain parts of southern Finistère or the Morbihan islands (such as Belle-Île-en-Mer), second homes exceed 60%, or even 70% of the housing stock.

This development is profoundly changing the real estate landscape: soaring prices, scarcity of properties for sale, and the proliferation of agencies specializing in seasonal rentals.

An economic engine... in the short term

The arrival of new homeowners can represent a short-term economic opportunity: renovation projects boost the local construction sector, local businesses benefit from summer tourist flows, and municipalities collect a higher housing tax on second homes. This phenomenon temporarily injects wealth into areas that are sometimes experiencing economic decline.

But these one-off benefits should not mask the structural consequences of this model.

Pressure on the local fabric and the balance of territories

Off-season desertification

One of the main consequences of the development of second homes is the desynchronization of local life . In many Breton communities, the population triples or quadruples in summer, then falls back to extremely low levels the rest of the year. Streets empty, schools close due to a lack of students, and public services withdraw due to insufficient attendance.

This phenomenon particularly affects rural or island communities, where a constant human presence is essential to maintaining a vibrant social and economic fabric. In winter, some villages become "ghost resorts," with few shops open and a loss of conviviality felt by the last year-round residents.

The gradual eviction of the premises

The influx of second home residents, often more affluent, has automatically led to a rapid rise in property prices . This pressure on land makes buying or renting very difficult for the original inhabitants, particularly young households, working people, or seasonal workers. Many Bretons are thus forced to leave their town, or even their region, to find affordable housing.

This process of residential exclusion causes a gentrification of territories , where the living environment is preserved, but emptied of its vital forces: teachers, farmers, traders, artisans or caregivers.

A social and economic imbalance

Beyond housing, the very social structure of Breton villages is affected. Secondary residents, absent for most of the year, participate only marginally in local community, cultural, or political life. Social ties are weakening, local solidarity is weakening, and intergenerational exchanges are dwindling.

By moving towards an economy centered on tourism and seasonal hotels, some villages are also becoming dependent on an unstable economic model , particularly vulnerable to health, economic or climatic crises.

What answers can be given to reconciling attractiveness and local roots?

Acting on political and regulatory levers

Faced with this situation, several Breton municipalities are experimenting with measures to regulate second homes . Some towns classified as "tense zones" now require prior authorization to convert a primary residence into furnished tourist accommodation. Others are opting for an increase in the housing tax, or for the introduction of quotas in new housing developments.

At the national level, the Climate and Resilience Act also provides for a limitation of land artificialization (Zero Net Artificialization objective), which requires better use of existing land rather than building at will.

Encourage residential diversity

It is crucial to encourage the settlement of year-round residents by diversifying the housing supply: development of social housing, rehabilitation of vacant housing, support for home ownership for young households or first-time buyers.

Municipalities can also encourage alternative housing models, such as participatory housing or intergenerational residences, which help rebuild social ties while addressing environmental issues.

Revalue local roots

Finally, we should not systematically pit second home residents against permanent residents. Some of them want to become more involved in local life. Initiatives are emerging: the opening of third places, community involvement, shared gardens, and village cooperatives.

By encouraging this involvement , municipalities can create bridges between different populations and re-anchor second homes in a living , rather than decorative, territorial project.

In conclusion, Brittany today finds itself at a crucial crossroads. While the appeal of its landscapes, heritage, and way of life is undeniable, it must not come at the expense of local life. Second homes, if left unregulated, risk transforming villages into soulless showcases, emptied of their residents, businesses, and vibrant culture.

The future of Breton villages will depend on their ability to remain places of life, and not of passage.